Delirium is sudden, acute or intense confusion and it can affect anyone when they are very unwell, but is much more likely in a person with dementia.

One of the challenges with identifying delirium is that it comes with very varied behaviour, but if you suspect delirium in any way, it is important you act on it.

It occurs suddenly, within hours or days, and can be very frightening for both the person affected and those caring for them.

It needs to be addressed and treated as early as possible as delirium can have serious negative consequences and one episode can increase the risk of further episodes, especially if it goes untreated.

This video is very helpful in explaining delirium:

Hyperactive delirium is the most obvious kind with very marked, sudden and major changes in how the person acts.

The person may be agitated or abnormally active. This may include constant monitoring of potential threats around them (hypervigilance), restlessness, rambling speech, loud noises, hallucinations, wandering, being distracted, irritable or showing low tolerance of frustration.

Due to confusion and anxiety, they may become defensive and react with verbal or physical threats against people who try to help them.

Hypoactive delirium is much less obvious. It is marked by a decrease in behaviour or physical activity.

The person may seem sleepy and inactive, speaking more slowly and being less aware of their surroundings.

It can often be mistaken for depression or a deterioration in a person who already has dementia, rather than a separate issue that needs treating.

A person may display a mixture of hyperactive and hypoactive delirium, switching between the two.

Carer's Question: My father can get quite mean and accuses his family of hiding things or stealing. This is so difficult and worrying.

DCC team response:

Unfortunately, one of the symptoms that people can have is that they become paranoid and start to believe that others are conspiring against them or trying to harm them. And they really believe that. It’s just the way their mind works at that point. It feels very real to them and nothing you say will change that.

Try to remember that this is just a symptom of delirium. Once you find out the cause and start treatment, hopefully it’ll stop or subside.

This is easier said than done, but you must try to take a step back and recharge your own batteries when these situations occur. It can be very emotionally draining to be accused of something when you’re doing your best.

Even if it’s just for a few seconds to take a deep breath. Try to talk to someone and share your feelings. If there is a family member who can help you, ask them to. Let them take over for an hour.

Risk factors

Delirium is not just a symptom of dementia and can be triggered by many other things, but a person with dementia is five times more likely to experience delirium than someone without.

Other common risk factors are:

- Aged over 65

- Several health conditions

- Infections (such as a urinary tract infection (UTI))

- High temperature

- Pain

- Side effects of or sudden stopping of drugs or alcohol

- Dehydration or low salt levels

- Liver or kidney problems

- Major surgery, especially hip and vascular surgery

- Constipation

- Use of an indwelling catheter

- Lack of mobility (often due to a fall)

- Unfamiliar surroundings

Things you can do for a person with delirium

The most important first step for a person with delirium is to recognise they are experiencing it.

Being aware of the symptoms, picking up on them and going straight to your GP is the most important thing you can do as a carer.

Your GP can then look into what might be causing the delirium and make sure it is treated.

Being aware of risk factors and making sure they are under control and treated is also important.

For example, if the person has a urinary tract infection or a high temperature, get it treated as soon as possible to help stop delirium from happening in the first place.

Over time you may become aware of the early warning signs of delirium in the person you are caring for, especially as you know their personality better than other people. It is good in this case to write these early warning signs down and pass them to anyone else who cares for them, in hospital or at home.

If the person is prone to bouts of delirium or one of their risk factors has come into play, make sure their environment is as calm as possible.

Good lighting and making sure they are wearing their glasses or hearing aid also helps.

A person experiencing delirium can become quite nasty or aggressive to the people around them or caring for them. They might accuse you of stealing from them or trying to hurt them in some way.

This paranoia is beyond their control, but if it is happening frequently, it can be very upsetting for you as a carer.

The best thing you can do in this situation, apart from getting the cause of the delirium treated, is to try and make sure you are getting some time out from caring for the person, giving yourself time to recover emotionally.

If this isn’t possible, even stepping outside of the room and taking a deep breath can help. Talking to someone about what you are dealing with can also make things feel more manageable.

The difference between delirium and dementia

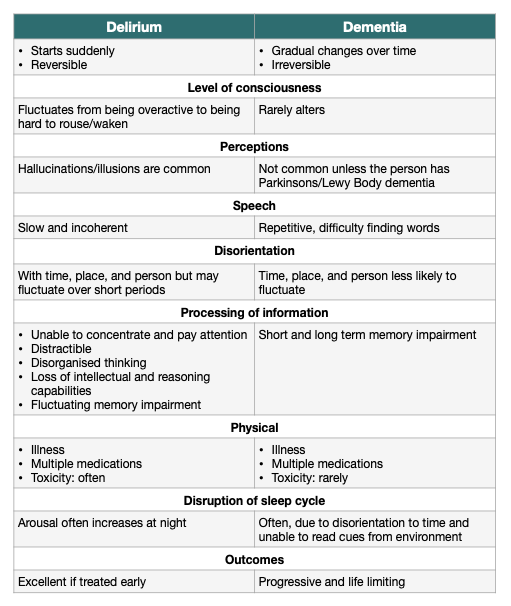

The difference between delirium and dementia isn’t always clear, even for professionals, because it’s possible that delirium happens on top of dementia, but there are some differences.

While dementia is an ongoing condition, with gradual changes over time, delirium starts suddenly and is reversible.

A person with delirium can fluctuate between being overactive and hard to wake. A person with dementia keeps a more steady state of activity.

Delirium frequently causes hallucinations or illusions, which is rare in someone with dementia unless they have Parkinson’s or Lewy Body dementia.

Speech may be slow and incoherent in a person with delirium, while a person with dementia tends to repeat themselves and have difficulty finding words.

A person with delirium may find it difficult to concentrate and pay attention and may temporarily lose their ability to reason while a person with dementia will suffer short and long term loss of memory.

Once the cause of delirium is identified and treated, it usually goes away, but the recovery time is different for each person.

If you suspect someone has delirium, then an assessment and appropriate tests should be carried out as soon as possible. There can be multiple triggers/causes which can make diagnosis and treatment complex, and this may take some time, so the earlier you seek help the better the outcome for the person.

Delirium diagnosed in hospital

If delirium is diagnosed in hospital, it’s very important that the person’s GP is informed of the diagnosis. The GP may need to follow up and monitor the situation in the community.

After a first episode of delirium, it’s very helpful to have a prevention plan in place to ensure that you recognise any early warning signs, seek treatment quickly and prevent escalation. Talk to hospital staff, your local GP or community mental health team who may already have specific care plans in place.

The effect of delirium on you as a carer

As a carer, delirium can have a big impact on you and your emotional wellbeing.

Knowledge really is power in these circumstances. So make sure you get the right information, keep up to date, ask questions and make your needs known by asking for a carers’ assessment.

Don’t be afraid to voice your concerns for the person you care for as they may not be able to, but also for yourself.